(This article was first published in Finnish and with different photos in Suomen Luonto -magazine 3/2015)

Plastic debris is already a global problem. A large part of it ends up in the oceans and disintegrates into micro particles in the ecosystems causing disaster.

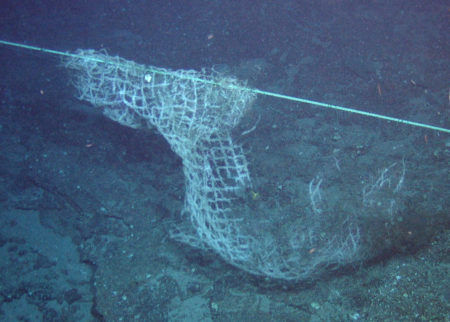

Remains of trawl on a remote beach in Tasmania. Discarded fishing equipment pose a long time threat to marine animals. Photo: CSIRO

Until last summer a young 154 meter long sei whale sieved its food, small crustaceans, from the open waters of the Atlantic. Accidentally it swallowed also a fragment of a dvd case, which tore its stomach. The whale swam to die at Chesapeake Bay in the east coast of the United States and could not be rescued any more.

This story is only one of thousands. It arose a lot of attention, because the species is endangered and the whale came to shallow waters in a populated area, which was unusual behavior for it.

The seas hide part of the rubbish in their secret sinks. Part of it ends up being the destiny of birds, fish, turtles, seals and other sea mammals. In addition to the ecological problems the sea debris hampers fishing, maritime, beach-residents and tourism.

In spite of the developments in waste management, the seas of the world continue to be the largest landfill on Earth. Marine researchers and environmentalists are vigorously trying to find ways to protect the richness of life in the oceans.

Extreme litter picking in the deep seas

Lucy Woodall researched deep oceans and found both large trash and microplastics. Photo: Auli Kilpeläinen

English marine and molecule ecologist Lucy Woodall videotaped the bottoms of the deep seas during the research trips of the London Natural History Museum. She was primarily researching the fauna of the seamounts, but found also other things:

– In the Atlantic we saw everything from a 17th or 18th century clay pot to wine bottles, modern fishing gear and plastic rubbish. In the Indian Ocean we found mostly fishing gear, and among other things also cast-off engine parts.

All ten research areas lay over 500 meters deep, and most of them more than 1000 kilometers off the shore. – Marine debris exists everywhere from the poles to the equator, from the shores to the open seas and from the surface to the bottom sediments, Woodall says.

The amount of rubbish ending up in the seas is estimated to be around eight million tons a year. Only long-lived materials are counted as marine debris, so the amount of rubbish in the seas grows larger year by year.

Deep sea fish with a rubber glove found in the bottom of the Indian Ocean. Photo:

ROV Kiel 6000 -IFM GEOMAR

A small part of the rubbish is visible to the eye and the vast majority is minuscule chaff, microplastics. The newest research by Woodall´s group demonstrated that both are accumulated in the seabed. The bottom sediments of different oceans contain huge amounts of especially fiber shaped microplastics.

Ghost nets may keep fishing for years

The loosely drifting ”ghost nets” and other escaped fishing gear might continue catching for years. The trash carried by the sea currents may also spread alien species to new habitats, where they invade space from original plants and animals.

Littering might be the last nail in the coffin of the most endangered marine species, states a report by the international Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). The report is especially worried of the critically endangered Hawaiian monk seal, the loggerhead turtle of the warm seas, the rare northern fur seal living in the north of the Pacific Ocean and the white chinned petrel of the southern seas.

What can researchers, consumers, organizations or governments do to stop the littering of the oceans? There is no definite global data of the sources and amounts of sea debris, but regional studies are made in many countries.

Surveying the quantity and quality of marine debris

Ecologist Denise Hardesty from Australia’s national science agency (CSIRO) managed the world´s largest systematic marine debris survey this far. The three year project financed by Shell surveyed the beaches of the whole continent. Transects, laboratory analyses and inquiries to local officials were done every hundred kilometers.

A grand waste management budget did not necessarily mean a low amount of beach rubbish. Investing in campaigns against littering, in recycling and in the waste management of the beaches reduced the rubbish clearly more than investing in waste management facilities.

Trash gathered from Australian beaches was separated and part of it studied in a laboratory. Photo: CSIRO

– The problem has to be solved at sources, not where the rubbish accumulates in the ocean and on beaches. Working together with industry partners, governments and private consumers for whole of life approaches to packaging would be a big step towards the solution, states Hardesty.

Alleviation with cleanups and super hoovers

The rubbish problem can be alleviated also in a traditional way: by cleaning.

Nicholas Mallos organizes coastal cleanups around the world. The ceramic cup reduces plastic trash. Photo: Auli Kilpeläinen

American marine biologist Nicholas Mallos from the marine conservation organization Ocean Conservancy says, that in the coastal cleanups organized by them all over the world during 27 years, over 200 million pieces of rubbish have been collected: cigarette buds, food wrappers, caps or lids, plastic bottles, plastic bags, beverage cans, rope…

Also large technical appliances have been planned for cleaning. Probably the most famous of them is the huge garbage trap originated by dutch student Boyan Slat. The sea currents would steer the rubbish floating in the waste gyres of the oceans to the device´s throat with the help of long beams. The machine would bale the waste, and the bales would be fetched ashore for recovery.

The Ocean Cleanup project lead by Slat has done pilot studies, replied the questions of critics and gathered crowdfunding for building a pilot unit.

It is most important, however, to prevent the escalation of the problem and to concentrate on the sources of waste: products, waste management and practices in all functions where rubbish gets lost.

Plastic bag bans are spreading

Most attention and restrictions of rubbish-generating products have been globally targeted at plastic bags. And for reason: according to one estimate two million of them are used every minute.

Kamilo Beach in Hawaii is known as a trash beach, where plastic debris from the Great Pacific Garbage Patch accumulates. Photo: Nicholas Mallos

The plastic bag tax of Ireland reduced the use of plastic bags to a fraction. Great reduction was achieved also in Australia, when a payment for plastic bags was imposed.

The state of California in the United States has decided to ban throwaway plastic bags in the next few years. Also the European Union accepted in November a directive obliging the member states to restrict the use of plastic bags. Perhaps a small act is one beginning in the cleaning of the vast oceans.

Microplastics sneak into foodchains

Chelsea Rochman researching how fish at San Diego Bay accumulate microplastics and toxic chemicals. Photo: Sarah Wheeler

”Marine microplastics are a novel media for the transport of chemical pollutants in the environment,” says marine ecologist Chelsea Rochman of the University of California. Rochman studied the absorption of toxic chemicals in plastic debris in the heavily polluted San Diego bay and the consequences to the health of fish eating this rubbish.

– We fed microplastic that had been deployed in the sea to medaka fish. More chemicals accumulated in the fish that ate it than in the fish that ate ”clean” non-deployed plastics or a non-plastic diet. Also liver damage and signs of endocrine disruption appeared in the fish that had eaten the marine plastic.

– Plastic debris accumulates chemicals from the water column and the sediment. It absorbs e.g. nickel, lead, PAH-subtances, PCBs and PBDEs (brominated flame retardants). Once in the food chain these chemicals are transferred from plankton to small fish and from them to the big predatory fish.

Rochman´s research team comments on the results radically: Classify plastic waste as hazardous substance to allow existing laws to begin to mitigate the problem!

The research on microplastics has intensified only a few years ago. Even the definition is unofficial: particles less than five millimeters of dimension.

Microplastics research on the rise

Now the research of microplastics is so popular, that senior researcher Outi Setälä of the Finnish Environment Institute (FEI), Marine Research Centre, says she gets messages of the subject weekly from around the world.

– The environmental consequences of marine debris and microplastics are a rising area of study internationally, says also Peter Kershaw, leader of the United Nations marine debris working group. Within the United Nations the subject is being researched and evaluated in co-operation by the Environmental Program (UNEP), The Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC-UNESCO), the International Maritime Commission (IMO) and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

Microplastics form when bigger rubbish disintegrates into small particles by the impact of waves, light and time. In addition minuscule plastic particles come from industrial waste waters and are dissolved from different consumer products like toothpastes, shampoos and skin scrubs. One wash of a fleece garment detaches over 1000 fibers in the water.

The great majority of microplastics is minuscule and can only be seen through efficient microscopes. The micro-sized particles are measured in thousandths of millimeters and the nano-sized in millionths of millimeters.

The FEI and The Helsinki Region Environmental Services (HSY), together with the City of Helsinki Environment Centre, have researched where microplastics come from and how much the Baltic Sea contains them. In the sea area around Helsinki they were found in all sieved surface water samples and in almost all sediment samples.

The FEI is trying to solve especially, how microplastics are carried in the lowest stages of the food chain. – When animal plankton unintentionally eats plastic particles, they can move further in the food web, says Outi Setälä.

– The chances of microplastics to be carried along the food chain have been testified in laboratory conditions. In free waters microplastics are still quite sparse. How much microplastics and the poisons they contain are accumulated in nature, is as yet a theoretical question.

Prevention is most important

Marine biologist Julia Talvitie is doing her doctoral dissertation at the Aalto University on how much of the microplastics can be removed in wastewater treatment plants and with which technology. Until now the removal of microplastics has not been taken into account when developing the treatment technology.

– For the rubbish visible to the eye, which accumulates on the shores, something can still be done, but it is impossible to collect back the microscopic particles that have ended up in water. That´s why their entry to the waters should be prevented.

Talvitie wishes for measures to restrict the sources of microplastics, so that the solution of the problem would not remain solely upon the consumers.

Fulmars reveal the state of the North Sea

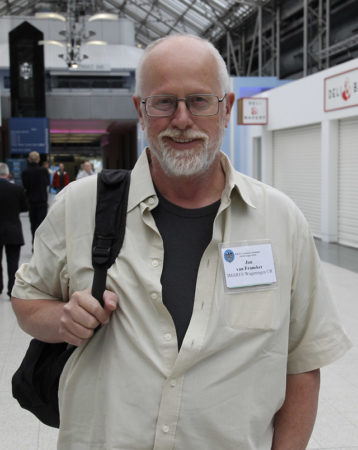

Jan van Franeker´s long-term bird monitoring reveals the problems of plastic debris in the North Sea. Photo: Auli Kilpeläinen

Marine ecologist Jan Van Franeker with his IMARES research group has monitored the state of the North Sea for over 30 years with the help of a common and important indicator, the northern fulmar.

– The northern fulmars prey from the surface of the sea and by mistake they feed on floating sea debris, mostly pieces of plastic. The plastics are slowly ground in their muscular stomach and accumulated in their body in balance with their intake of debris.

According to van Franeker this makes the northern fulmars a good indicator of the prevalence of plastics in the sea – but hampers their feeding, weakens their health and may finally kill them.

Fulmars are excellent divers and swimmers. They can live up to 30–40 years, but marine debris often kills them prematurely. Photo: Jan van Franeker, IMARES

The IMARES research group (Institute for Marine Resources & Ecosystem Studies) works in Wageningen, Holland. The group collects and analyzes regularly the dead fulmars, which have drifted on the coasts of the North Sea.

The newest survey revealed plastics in the stomachs of 95 % of the birds, 33 small fragments on the average. In relation to body weight, this would mean a hundred times more for humans.

Left: average amount of plastic trash in the stomach of dead fulmars. Right: same amount scaled to human size. Photo: Jan van Franeker, IMARES

– The amount of rubbish in the North Sea has not changed much in the 2000s. Even though the waste politics and the protection of the seas have developed, the increase in shipping and use of plastics have invalidated their effect.

Van Franeker says that the EU-accepted target of the good state of the seas by the year 2020 cannot be reached at this rate.

Text: Auli Kilpeläinen

Photo copyrights: see captions

- The Invaluable Doñana Wetland Facing Threat of Drought – 2019

- Neonicotinoids – Even PPBs Are Too Much for Insects – 2019

- Ecologists Defend the Invaluable Doñana Wetland – 2018

- European Mink Returns to Estonia – 2016

- Diving for Marine Protected Areas – 2015

- Organic Gardening Inspires Youngsters in Northern Spain – 2015

- Plastic Debris Spoils the Oceans – 2015

- Only Cute and Cuddly Are Worth Conserving? – 2014

- Gilbert´s Potoroo Was Rescued on an Australian Island – 2014